Menopause: the architect of a new brain structure

Women have long been told that midlife brain fog, insomnia and mood swings are “all in their heads.” New research shows this is true, but not because it is imagined.

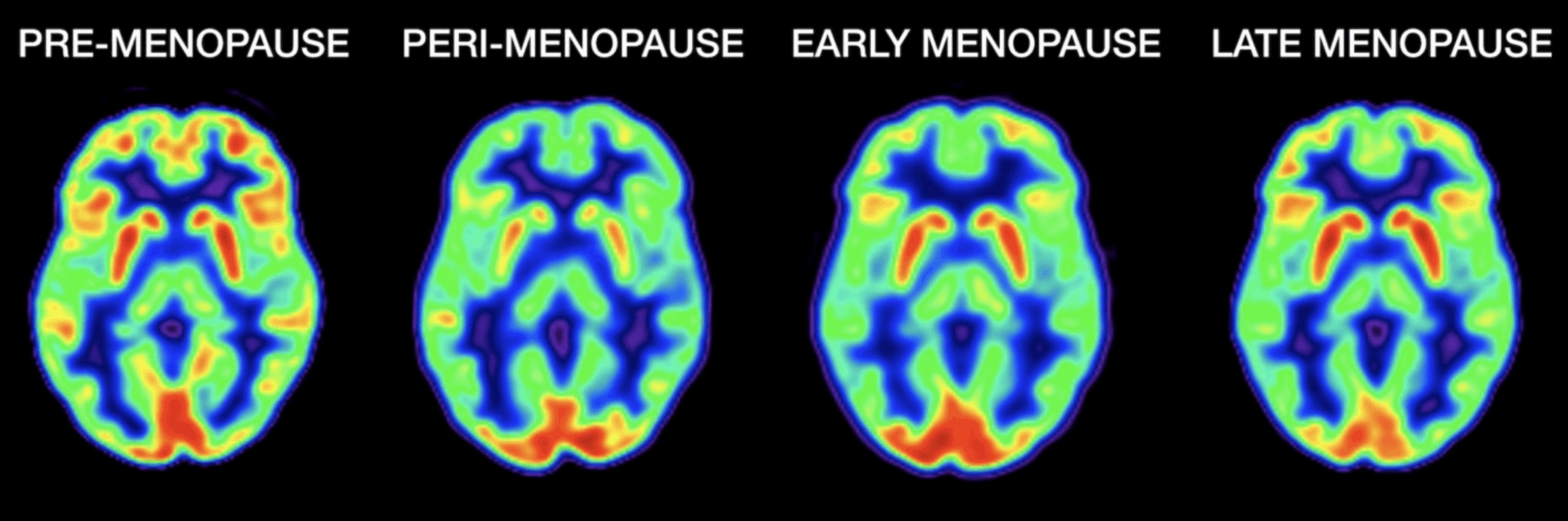

Brain scans carried out before, during and after menopause reveal dramatic physical changes in structure, connectivity and energy metabolism. These changes are not only visible on the scans, but many women can also feel them, says Dr Lisa Mosconi, a neuroscientist and author of the book “The Menopause Brain.”

Gray matter volume is reduced in areas of the brain involved in attention, concentration, language and memory, and there also are changes in connectivity. Areas involved in reproductive functions become less connected, while other regions become more connected. There are declines in brain energy levels, meaning the brain pulls glucose from the bloodstream and does not burn it as efficiently as it used to.

Using various neuroimaging techniques, the brains of more than 160 women between the ages of 40 and 65 who were in different stages of the transition were studied by Dr Mosconi’s team.

They also imaged the brains of men in the same age range.

“What we found in women and not in men is that the brain changes quite a lot,” says Dr Mosconi. “The transition of menopause really leads to a whole remodelling.”

On average, women enter the menopause transition – defined as the first 12 consecutive months without a period – at around 50; once diagnosed, they are in post menopause.

Brain scans from women 40 to 65 years old show glucose levels dipping during perimenopause and then stabilising or increasing in some areas postmenopause.

Photo: Dr. Lisa Mosconi/Weill Cornell Medicine

What does this mean for Dementia?

Women experience a loss of both gray matter (the brain cells that process information) and white matter (the fibers that connect those cells) post menopause. However, that loss stops, and in some cases brain volume increases again, though not to its premenopausal size.

The researchers also detected corresponding shifts in how the brain metabolised energy, but these did not affect performance on tests of memory, higher-order processing and language.

This suggests that the female brain goes through this process, and it recoups.

Understanding what happens in the brain around the time of the menopause transition could inform how to treat symptoms.

Hormone therapy – whether estrogen alone or in combination with a progestogen – is not ordinarily prescribed until post menopause, and carries risks; on the other hand, it can help treat symptoms.

Some women who receive hormone therapy might also gain cognitive benefits, but more evidence is needed to identify who should be treated. Randomised control trials of postmenopausal women have tried to assess whether hormone therapy decreased the risk of Alzheimer’s disease, but these have returned mixed results so far.

Dr Mosconi found that women who had a genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease began to develop amyloid plaques, which are linked to the disease, during perimenopause in their late 40s and early 50s – earlier than previously thought. If the brain changes significantly during perimenopause, it’s an important time to take measures to prevent Alzheimer’s and other chronic diseases.

Several major chronic diseases, including Alzheimer’s, appear to afflict women disproportionately. More than two-thirds of those diagnosed with Alzheimer’s are women (only in part because they live longer, and older people are at greater risk).

Women are at twice the risk of developing a major depressive disorder, and cardiovascular disease – which is also a risk factor for Alzheimer’s. Identifying why those health disparities exist and what to do about them will require researchers to consider sex and gender specifically as variables, which science has been slow to do.

The stress factor

Research indicates that chronic stress leads to brain shrinkage and reduced memory performance by the 40s and 50s, which is more pronounced in women.

A key reason is cortisol, the stress hormone. Both stress and sex hormones are produced by pregnenolone.

Stress causes the body to use pregnenolone to make cortisol instead of testosterone or estrogen. That’s a problem for women because they already experience higher stress levels than men at every age. This peaks from 35 to 44, in the “juggling everything years.”

Perimenopause is also sending estrogen levels down; the combination of factors can lead to earlier menopause or make menopausal symptoms worse.

A 45-year-old woman has a one in five chance of developing Alzheimer’s during her remaining life, while a man the same age has only a one in 10 chance. Women seem to start getting the disease earlier, around menopause.

Classic symptoms that start in perimenopause – mood swings, depression, anxiety, “brain fog,” disrupted sleep, memory lapses, migraines and even hot flushes are signs of the brain being in transition and needing extra support.

There are a number of possible measures to protect cognitive health before and after the menopause transition, including not smoking, keeping active, eating a plant-rich diet, reducing stress and getting enough sleep.

Menopause is a critical window when a woman might begin to develop the first signs of chronic disease, so it’s an important time to check in with her GP.

This article was originally published in Our Mind Matters Magazine Issue #43.