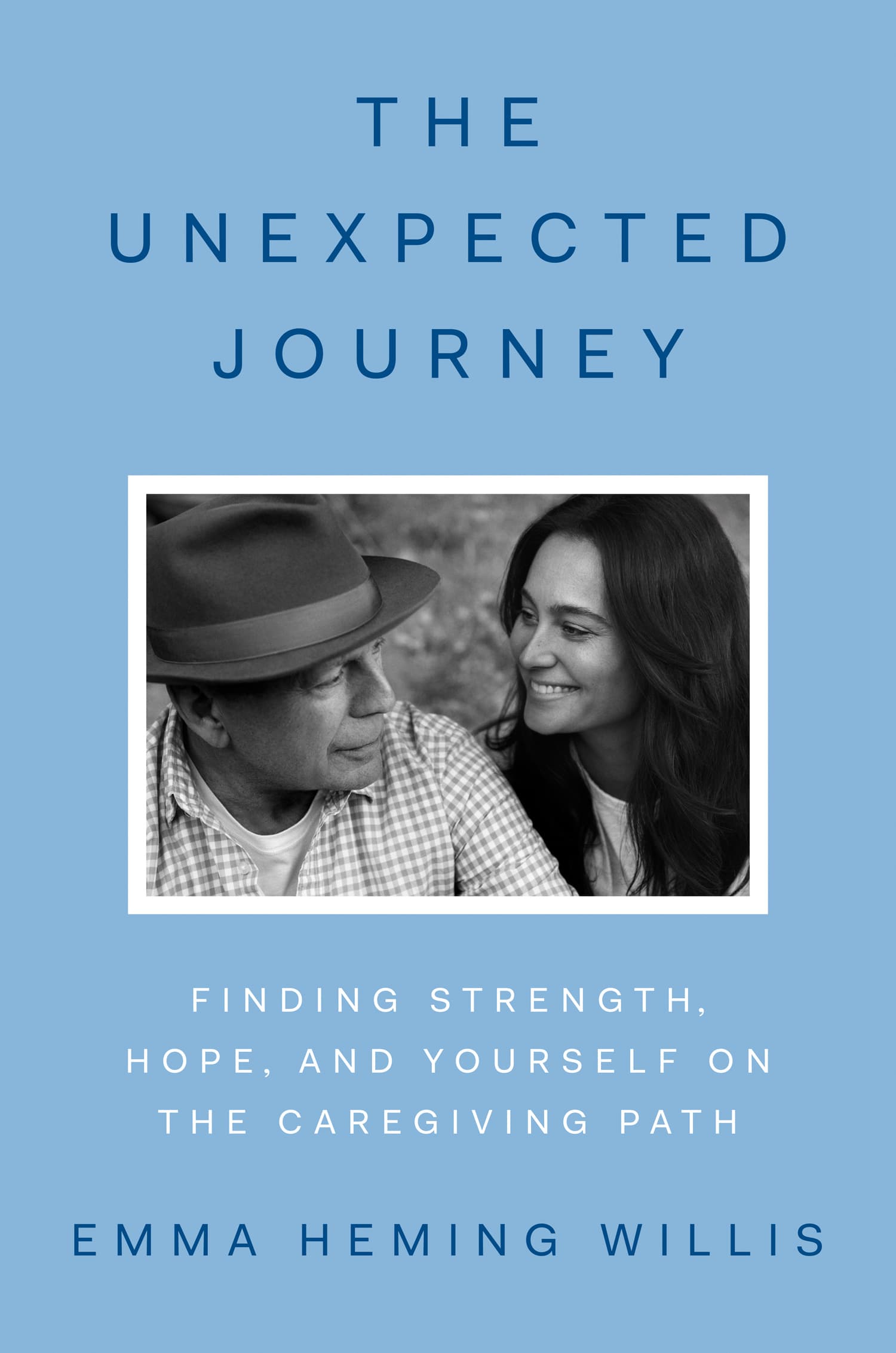

Book Review: The Unexpected Journey by Emma Heming Willis

By Nicola Williams

We know dementia doesn’t discriminate. Yet, when one of the world’s most successful action stars becomes affected, it still seems such a disconnect to pair a person who was the epitome of physical and mental fortitude with a disease eroding his every ability.

Of all the stories Bruce Willis has brought to life on our screens, this chapter of his real life is by far the most powerfully emotive; this ending will not be one where he will be able to triumph over his adversary as we have come to expect from a Bruce Willis story.

The actor’s devoted wife Emma Heming Willis has written the book she wishes had been placed in her hands when he was diagnosed with Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD), serving as a roadmap to other care partners. Although she speaks specifically about their experience with Frontotemporal Dementia, she explores themes universal to carers of all forms of dementia.

Coming to grips with the diagnosis, how to build your support system, how to find that elusive time to yourself, the array of emotions encountered, coming to terms with having outside help when required and how to foster your own brain health are all topics covered with raw vulnerability.

Instead of being armed with the insight this book would provide anyone new to their unexpected journey, Emma was given only a pamphlet when dropped into her bewildering world. She has utilised people’s interest in their lives to do a great service to anyone else following in her footsteps, by offering a glimpse into their personal experience, while collating research from dementia and caregiving experts.

Despite fame, fortune and resources, the family’s experience is entirely relatable to the average person. She spoke of her fear of judgement from being so transparent but decided that opening herself up to the firing line of public opinion was a trade-off worth making to help reduce stigma.

Frontotemporal Dementia is often slow to be diagnosed because it starts with shifts in behaviour and personality, as opposed to a more obvious sign like the memory loss associated with Alzheimer’s.

“They assume their person is being rude, apathetic, withdrawn, depressed, irritable, impulsive, or reckless, or they lack empathy – an array of behaviours seen to be personal choices rather than symptoms of a disease.”

This shift in alignment with the character of the man she married and their previously shared outlook had Emma contemplating divorce. Bruce was becoming more withdrawn, which was put down to hearing loss that made it harder for him to engage in conversation.

Emma talked about the challenge of raising issues with Bruce’s GP, as she struggled with the morality of going over his head – sentiments expressed to us everyday by carers.

“If your feeling gets stronger that this change in behaviour is something that person can’t help, you have to trust that feeling because you’re actually acting to benefit your partner.” she says.

Often Frontotemporal Dementia is misdiagnosed as a midlife crisis, depression, or bipolar disorder – to name a few.

Bruce was initially diagnosed with Primary Progressive Aphasia, a condition where 75% of cases will go on to develop Frontotemporal Dementia, as he did.

Emma talks about “our diagnosis,” acknowledging that although Bruce was the one with the disease, the whole family carry the weight of it. However, once she realised the change in her husband was beyond his control, she quickly fell in love with him again, in a profound and unconditional way. Their future together was no longer in question, despite it being vastly different to the one they had imagined. As Bruce declined, the grief and loss of losing parts of such a wonderful husband and father was palpable. Emma grappled with the paradox of referring to their life in past tense when Bruce was still present.

Perhaps one of the most useful chapters of the book is where Emma writes to the family and friends of care partners, articulating what many may struggle to when met with well- meaning but misguided conversations.

It resonates strongly as I hear many care partners voice the same frustrations around issues like receiving unsolicited advice. Taking a copy of this page and handing it out to the people in your circle may help prevent unhelpful conversations or put the breaks on them without having to have an awkward conversation to address it.

Emma explores the realisation of the importance of filling her own emotional tank to avoid becoming completely depleted. She found things that would nourish her soul while keeping her close to home and offers suggestions about how to do the same. For her one of these activities was gardening, and it soon became her happy place. The safe escape helped her hyper-vigilant nervous system settle a little. Caregiving situations tend to gradually intensify over time, which is why most caregivers don’t realise they’re becoming consumed by the increasing demands of the process. But the enemy of self-care is ever-present: guilt. Emma offers ways to reframe these thoughts.

“You can be someone who is grieving AND be someone who enjoys time with a friend”

“Would my loved one want me to live without joy? Is that honouring the person?”

Her words are comforting and cathartic, like a therapist who validates your feeling throughout, acknowledging the magnitude of the job the reader has stepped up to do and offering praise in an often thankless job.

One of the hardest parts of her story to reveal was the decision for Bruce to live a separate house to his family. While for most people, this would represent a move to a residential care facility, the family had the financial means for him to live in a house nearby with all the care he needed. This became necessary due to the contrasting needs of two children and someone with progressing dementia. Bruce needed a quiet, calm environment, which did not lend itself to his daughters being able to do things they enjoy. It became necessary to live apart to be able to meet the needs of both.

Emma felt this was the part of the story that would bring the most judgement and she grappled with guilt. She arrived at the position that ”love isn’t measured by where care happens but by the care itself”

Empahetic distress added to the emotional toll.

“Empathetic distress is feeling distressed because you’re overidentifying and projecting what your loved one must feel like. It’s imagining that if I were Bruce, I would feel this way because you’re seeing him as having the same brain as you and the same experience as you. So you’re thinking, He must be lonely, and then that breaks your heart. And yet that isn’t his experience.”

Emma encourages caregivers to reach out to a support group like those offered by Dementia New Zealand.

“Much about caregiving is irritating, unattractive and upsetting. Expressing those feelings does not disrespect the loved one you’re caring for but validates your own suffering, sacrifice, and humanity in the caregiving relationship. You have the right to your own emotional process, and it’s essential to engage it for your long-term well-being.”

The book is now available in all leading bookstores.