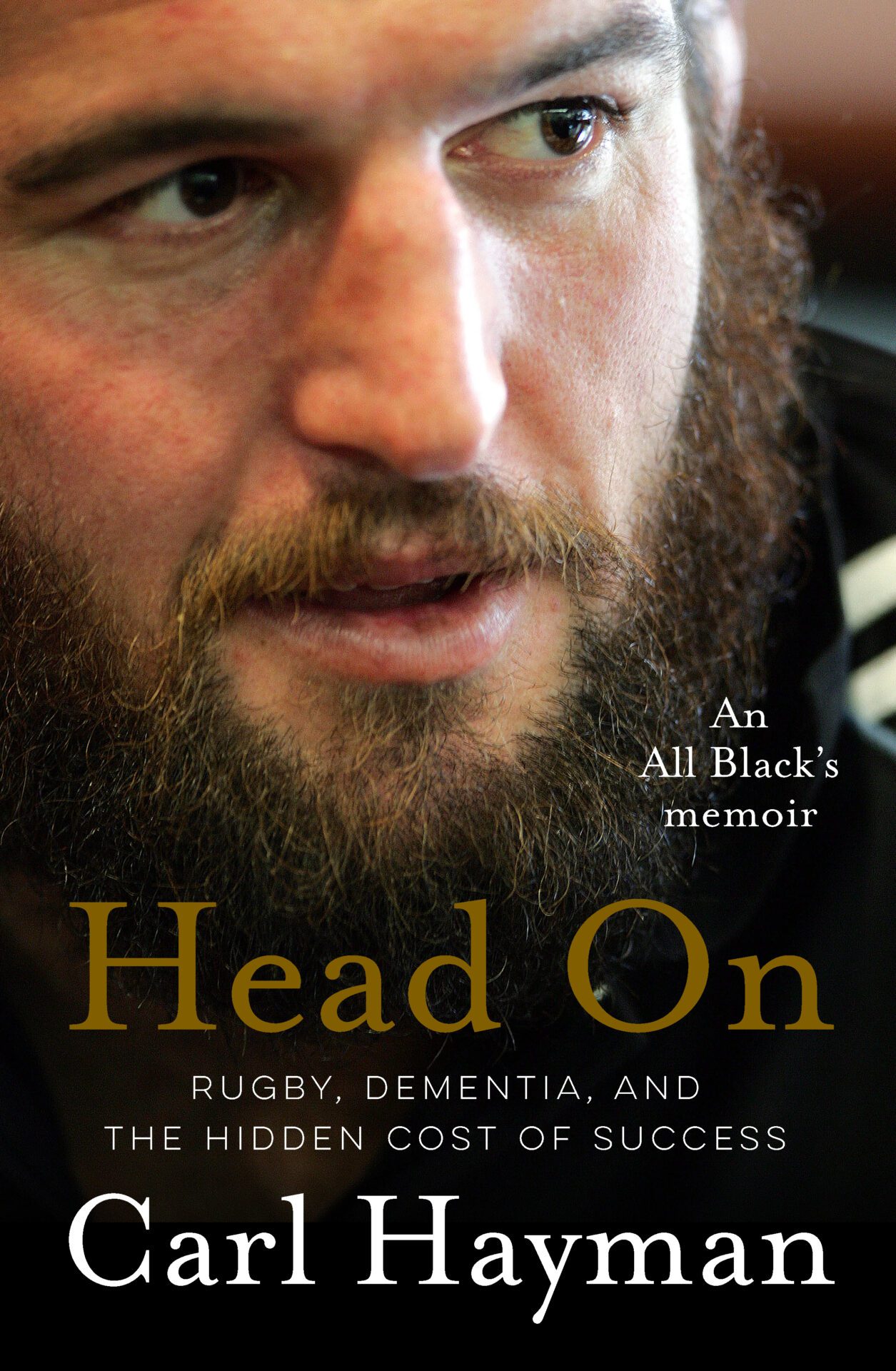

Book Review: Head On By Nicola Fletcher-Williams

Once estimated to be the highest paid player in rugby, Carl Hayman was experiencing the dizzying heights of success. But the very vehicle that put him there – the sport he was passionate about – was slowly and cumulatively causing a spiralling decent. The price he paid for every victory, accolade and pay cheque was profound, as now at age 43, he is grappling with Dementia.

Carl Hayman is doing what John Kirwan did for Depression – getting an often-stigmatised disease talked about with the help of their star power and willingness to be vulnerable and exposed, despite their lived experience being in a culture not about showing weakness.

His memoir Head On is a “living, breathing, suffering, cautionary tale” about the risks of contact sports. The known concussions were only the tip of the iceberg, as he estimates that throughout his 17 years as a professional rugby player, he took around 150,000 sub concussive blows. These do not meet the threshold to be classed as a concussion, the lack of symptoms makes the more minor damage go undetected, but each impact leaves it’s fingerprint until collectively they paint a devastating picture on an MRI scan.

Few people will get to relate to the adrenaline of roaring crowds and celebrity Carl experienced, but when it comes to the emotional journey of dementia, it is something that vastly more people can feel connected to, and have their experience reflected by. In his strikingly honest account, he wrestles with all the same issues as a large percentage of our population – such as the conflict about pursuing a diagnosis. On the one hand providing the validation that his emotional lability was due to a force bigger than him, conversely if it was explained by a diagnosis of Dementia, he thought it was perhaps better to be oblivious to it.

When things started unravelling while he was coaching in France, it was a frustrating process to get answers. Being In his 30s, Dementia was not the obvious explanation, and not one that would be good PR for the rugby industry. It was many a time explained away as depression.

But depression doesn’t turn a gentle giant into a man who would ever strike his wife, or account for his inability to remember conversations from five minutes ago and a raft of other cognitive deficits characteristic of Dementia.

He painfully describes how he could remember each of his 45 test matches well, but not what he did yesterday. He was eventually diagnosed in London with Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) which he understood to be a type of brain injury. It was not until he read a New Zealand Herald article about himself that he realised it was a type of dementia.

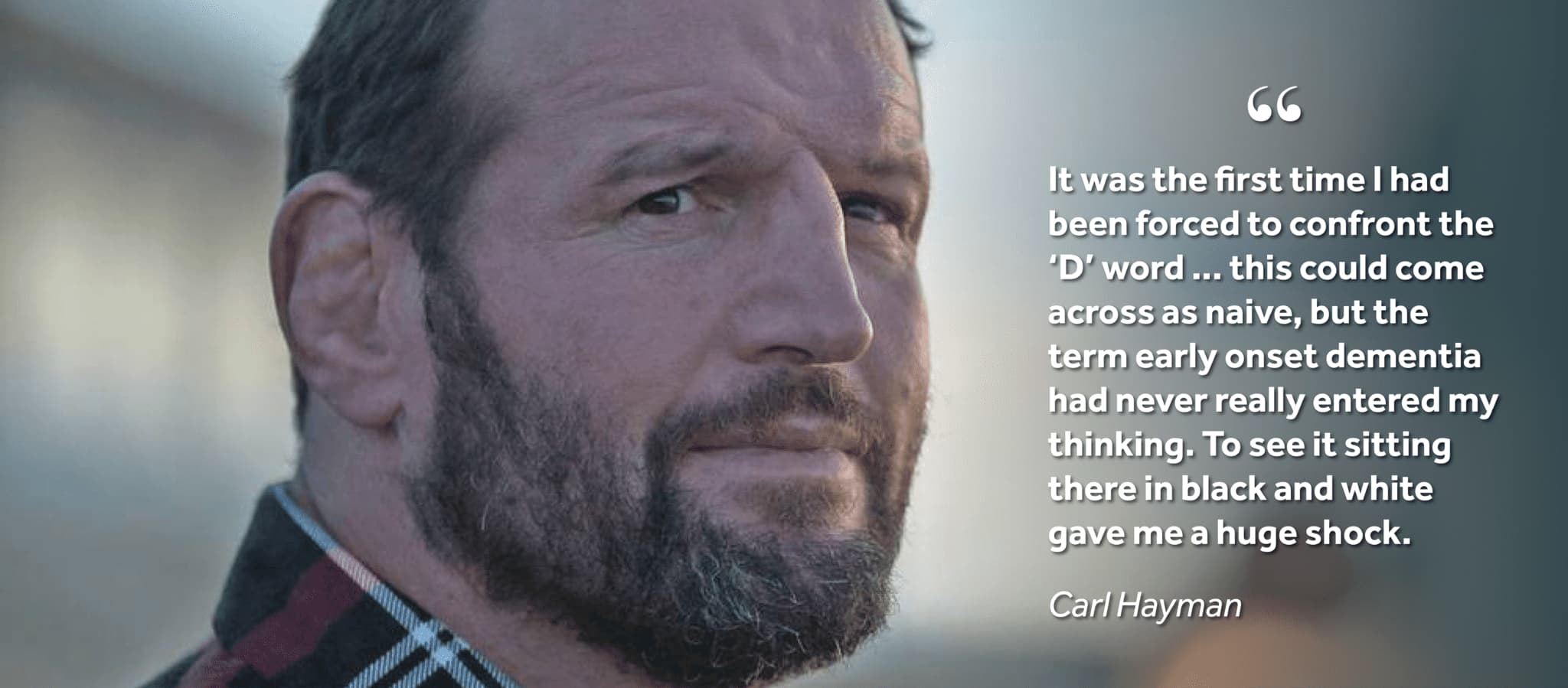

“There was a really problematic line in that story. It was the first time I had been forced to confront the ‘D’ word. It might sound implausible, but after all the testing, and perhaps because I’d heard so much about what was happening in the US around the NFL, I was almost hyper-focused on the term CTE.”

He rang his lawyer to find out if it were true that he had early onset dementia. What followed was a toxic cocktail of alcoholism mixed with a neurogenerative disease – each time he reached for alcohol to placate how he was feeling it only exacerbated his decreasing ability to regulate his emotions. This in turn lead to behaviour he regrets and the demise of his marriage.

When he relocated to New Zealand with a new partner, he struggled to get tangible support.

“I was beginning to feel the sort of rage you feel when you’re impotent against the system. I wanted the Accident Compensation Corporation to recognise that the problems I was facing on a daily basis were due to my profession, to the sport I played and loved, but I just kept hearing that I was depressed because I was going through a bad divorce and once I was all clear of that, I’d bounce back and be fine. Try living inside my head and then see how that assessment looks.”

He is part of a group of former rugby players taking legal action against World Rugby for failing to protect them from brain injuries. They take issue with the fact that World Rugby won’t accept growing scientific research showing constant head knocks is causing CTE.

Carl, however, is doing his part to raise awareness of the issue through his book, media appearances and his work as an ambassador for Dementia New Zealand. His book is perhaps a confronting read for anyone who has played contact sports who may be thinking about their own risk of dementia. It may be comforting to those also experiencing early onset dementia, in that he is helping the public to understand what they are going through. Carl is to be commended for his bravery in being able to share the details of his life he would probably rather emit. He is championing the cause Head On, and maintains that through everything, he is not without hope.