The grief and heartbreak of dementia

By Richard Walker

Alison and Neil Fagan in their Hamilton garden.

MARK TAYLOR / Waikato Times

Hamilton couple Alison and Neil Fagan had an overnight trip to make to Auckland. It was complicated because of Covid lockdown, and they’d had to get the appropriate paperwork.

The trip was to meet a specialist geriatrician, the next step in a longer journey, as Alison sought a diagnosis for Neil’s declining powers of cognition.

Neil loaded the car for the drive north. He put the suitcase in one car, and the food box in the other.

Dementia is not only about memory, Alison says, it is also about cognition. As inconsequential as it may seem, Neil putting their luggage in two separate cars was yet another pointer that something was up.

At 75, the former civil engineer is among the 8% of those 65 or older living with dementia, a number that is on the increase as baby boomers age, presenting an obvious social and economic challenge to New Zealand.

But when, like Neil, you are intellectually gifted enough to be a Mensa member, the signs of cognitive decline are not immediately obvious.

He has effortlessly passed the standard tests for dementia. If you’re down at 15 out of 30 on a so-called mini-ACE test, you’re likely to lose your licence. But if, like Neil, you get up to the high 20s, the GP and even the geriatrician may think everything is fine.

That was the challenge Alison, 70, faced. The trip to Auckland came out of frustration, a further attempt to get a diagnosis for Neil.

It’s one thing for a partner to know – and they know for a long time, Alison says – it’s another to convince the medical establishment. “A lot of the anecdotal evidence that I was presenting of my concerns was being ignored.”

An MRI scan showed changes in the brain structure which could have been normal pressure hydrocephalus, potentially fixable by putting in a shunt, she says. That was eventually ruled out by a second MRI. “They said, ‘It’s all right, it’s just Alzheimer’s’.”

It took over a year but finally Neil was diagnosed.

The key, Alison Fagan learned, was to write everything down. “If you can go to a doctor or a specialist with concrete examples, it’s much more beneficial than saying, ‘Oh, he’s a bit forgetful’. Just write things down.”

It’s been two years since Neil’s diagnosis, and that has also been a challenging time. Part of that is around negotiating the bureaucracy. Part of it is around the emotional ride.

Alison Fagan speaks crisply and clearly. She has been a maths teacher, and taken on high-powered roles including writing countries’ maths curriculums. Neil is not the only one in the family with a formidable brain.

The couple have been inveterate world travellers, chalking up more than 90 countries together, including working stints. They once got around five museums in one day but, as nerdish as that sounds, have also backpacked and taken risks. Like sleeping at an altitude of 16,000 feet in Tibet without oxygen. Like setting off across Africa by truck with no support.

They have done all this together in 50 years of married life.

And now they must stop.

Dementia is on the increase as the population ages.

Dementia, the best-known forms of which are Alzheimer’s and vascular, is on the increase in New Zealand. An estimated 1.4% of people were living with the condition in 2020, according to an economic impact report prepared for Alzheimers New Zealand. The figure was 8% among those 65 or older, almost one in 12.

By the year 2050, the proportion is projected to increase to 10.8% of the population aged 65 plus. That would mean more than 167,000 people living with dementia, effectively the current population of Tauranga, and more than twice the 2020 number.

And that in turn means more pressure on care dollars, more pressure on facilities, more pressure on the partners and family who shoulder much of the load.

The total cost of dementia to New Zealand is projected to more than double to $5.9 billion by 2050.

The health care costs were estimated at $25 million in 2020. Social care costs were estimated at $1.39 billion, of which $1.21 billion was the cost of aged residential care, a number that has been rising rapidly.

The hidden cost is the million weekly hours of unpaid care, provided mostly by family members, with an estimated 70% of people with dementia living in the community, rather than in residential care facilities.

Neil and Alison Fagan still live together in their north Hamilton brick and tile bungalow, and Alison would like to keep Neil at home as long as possible.

But in some ways he is already leaving.

Neil Fagan: I don’t feel happy about it, but I don’t worry about it.

MARK TAYLOR / Waikato Times

Soon after the diagnosis Alison got grief counselling, thanks to a referral from Dementia Waikato.

“The whole journey is actually a grieving process. You’ve lost your partner, even if they’re still alive. You’ve lost the partner you married, you’ve lost the partner you’ve lived with.”

Alison, a true mathematician, is clear-eyed about the condition, skipping the denial stage. She did go through anger, though. “Also, I think, because of the sort of person I am, I find it hard when he gets things wrong.”

Neil himself, bedecked in dressings after a skin cancer procedure, is serenely untroubled by his Alzheimer’s. “One of the advantages of being reasonably intelligent is you can put it all in perspective, and you don’t get sort of too distraught by it,” he says.

“I think it’s easier on me in a way – it’s harder on Alison, but it’s easier on me because I haven’t lost my marbles as it were. So I’m not in a daze all the time and I know what’s going on, I can keep up with the news and that sort of thing.”

Neil is on sure ground when recalling his and Alison’s life together, living in Africa for five years, Turkey for two, when they volunteered teaching refugee children, and the Cook Islands for two.

He was brought up in Porirua, has played competition bridge, and done race walking. These days he’s less steady on his feet and walking is limited to taking their border terrier, Rafa, out in the evening. That is likely to be followed by the day’s cryptic crossword, which he still successfully completes.

In the more immediate past, this morning, Neil was at a group run by Enliven, which involves a mixture of brain activities, games and quizzes.

“I do see people through the groups and things who are in a very different state. And that’s quite sad because they don’t know quite where they are.”

How does he feel knowing that he will probably end up like them?

“Well, I don’t feel happy about it, but I don’t worry about it. There are things you can do and there are things you can’t do, things you can change and things you can’t change.”

He laughs: “I’d say, don’t get it if you can avoid it.”

Alison Fagan says the bureaucracy can be hard to navigate.

MARK TAYLOR / Waikato Times

There is help for those with dementia, and for their carers, but it’s not always easy to find. From the outside, support in Waikato for carers and people with dementia appears fragmented, and Alison Fagan describes the bureaucracy as “horrendous”.

GPs and nurse practitioners can diagnose dementia, though they may also refer to a hospital geriatrician or, in some cases, the memory service or a neurologist.

But there can be an element of luck as to whether the diagnosis comes with a referral to either funder Disability Support Link, commonly known as DSL, or support organisation Dementia Waikato.

The Enliven group attended by Neil comes courtesy of funding approved by DSL, which assesses people’s needs. The day programmes are a big help, but were not easy to navigate as the offering kept changing, Alison says.

Respite care may also be available, though she says it can also be a minefield to navigate, with availability tight.

Alison has found a support group run by Dementia Waikato helpful, and also attends a women-only group.

“It’s people who are going through the same journey that gives you the biggest support. No one else actually understands,” she says.

First timers often vent. “It’s like a catharsis. They’ve never been able to talk about it before. It all just comes out.”

She speaks highly of Waikato woman Suzy McPhail, who has set up art and music sessions for people with dementia, and a monthly lecture session for carers, as well as running social events.

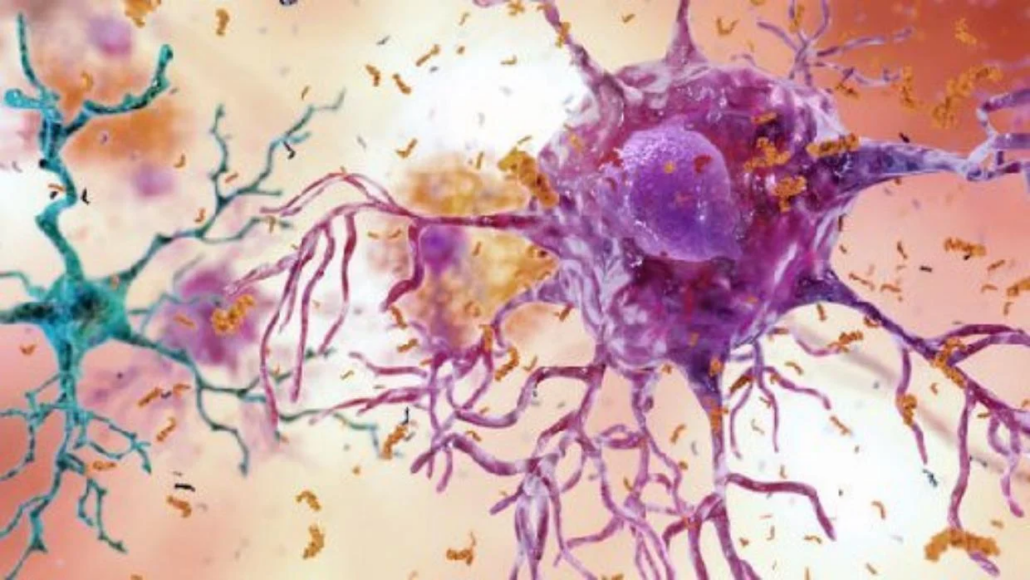

This illustration depicts cells in an Alzheimer’s affected brain, with abnormal levels of the beta-amyloid protein clumping together to form plaques, brown, that collect between neurons and disrupt cell function. Abnormal collections of the tau protein accumulate and form tangles, blue, within neurons, harming synaptic communication between nerve cells.

NATIONAL INSTITUTE ON AGING / Source: National Institute on Aging

Another stalwart of the scene is Robyn Riddle, who runs a long-standing women’s support group.

Hamilton woman Jackie Pinfold, whose husband of 54 years Dave was diagnosed 10 years ago, joined Riddle’s group, which she knew about through friends. She was working at the time, so the daytime Dementia Waikato groups didn’t suit her.

“It’s been great, and a lot of women that come through that group say they wouldn’t have coped without it,” Pinfold says.

She and Dave also attended a living with memory loss course, run through the DHB, which they were put onto when he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s at the head injury clinic 10 years ago.

Dave was also put onto a “blokes group” run by Enliven, and joined McPhail’s art and music programmes.

But Jackie is aware of how hard it can be to get information and support. “I’m more than happy to talk to people about what’s available. Because it’s frightening when you don’t know, and you wonder what’s ahead of you. I mean, there are parts in the care when you think, ‘if it ever got to that stage I’d be putting them in care,’ but when you get to that stage, it’s just the next little step. So you just do it.”

For Jackie, however, she finally had to have Dave put into care on November 22 last year.

Jackie Pinfold holds a photo recalling happy times with husband Dave.

MARK TAYLOR / Waikato Times

Dave was – is – a friendly, easygoing man, a former Waikato rugby rep and builder. But he suffered two brain bleeds after being struck by a roof truss just over 16 years ago, and surgery failed to get him on the path to recovery.

He was finally referred to the head injury clinic and diagnosed three days before his 70th birthday.

Initially it wasn’t too bad, Jackie says. It was almost like a badge of honour for Dave, who would tell everybody he had Alzheimer’s, which made it easier for others, she says.

Dave lost his driver’s licence but could still ride a bike. She was still working fulltime as a head kindergarten teacher before getting to the point where she had to stop.

They moved into a north Hamilton retirement village a couple of years ago, which Jackie describes as the best thing they could do.

“It’s been so supportive,” she says.”Everybody was very fond of David. I mean, he’d often be brought home again by somebody around the corner.” She laughs.

“I’ve been super lucky with all of my support. Family, friends, neighbours, everybody, because Dave was so likeable.”

And there has been humour along the way. She recalls phoning him from work one day to ask him to bring her lunch, which she’d left at home. Please don’t wear your old clothes, she told him, and be careful biking.

“After a while he arrived, big smile on his face, and he had this huge worker’s coat on with marks all over it. I said, ‘where on earth did you get that?’ And he said, ‘Oh, I saw a guy on the side of the road and he liked my coat, so we swapped.’

“To this day. I’m not sure which coat he swapped. But I suspect it might have been a leather one.

“He did cause us some laughs, honestly. Yeah, but he was a darling. He is a darling.”

There has been humour, but also heartbreak, for Jackie Pinfold.

MARK TAYLOR / Waikato Times

As important as humour is, there’s no getting away from the heartbreak.

She chooses her words. “It’s been sad, hard, awful.

“The worst part was, as it progresses, you lose your marriage as it was. So the physical side, the mental side.”

Discussions stop, a lot of companionship is lost. For a long time they could still laugh, but even that ended as Dave’s frustration and anger with his condition grew.

“He kept saying, ‘I don’t know what’s happening, it’s all mixed up’.”

Eventually, in his frustration, he lashed out physically. A friend who turned up soon after found Jackie sobbing. She told Jackie she wasn’t safe, and they took Dave to a Hamilton care home.

“He did cry a lot when he first went in, we both cried a lot. Because he knew something was different.”

But something perhaps surprising has happened, without the worries at home, including the need to help him physically.

“Now I don’t have to worry about all those sorts of things, I can just visit him in love.”

Alison Fagan, meanwhile, says Neil has become quite insular. She thinks that’s part of Alzheimer’s. “It’s too hard to interact. It’s too hard. So they switch off. And one of the hardest things is when they don’t show concern for you, or for a family member that’s having a problem, like there’s no empathy anymore.”

She doesn’t think it’s that they’re focusing only on themselves, more that there’s a limit to how much they can deal with.

In her case, a tough moment came when she had a painful fall, breaking a bone in her foot. “I said, ‘I’ve fallen and hurt myself,’ and Neil just kept walking. That was actually worse than the fall. No concern, you know, and that’s what you lose.”

Alison Fagan follows up our interview with an email.

“I remembered the most important thing I wanted to say,” she wrote.

“The most upsetting thing anyone can say is ‘Oh, Neil seems fine.’

“I am going to make a bulk order of T shirts that say ‘Don’t tell me my partner is fine until you’ve lived with them for 24 hours’.”

Dementia Waikato can be contacted on 07 929 4042.

This article was originally published in